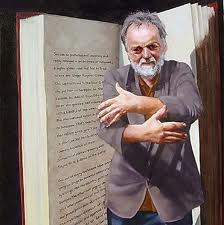

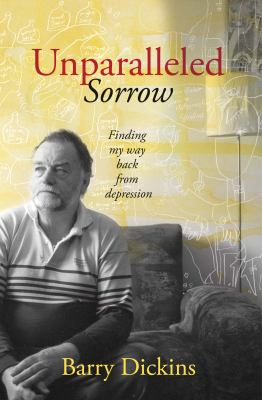

In 2010, I sat down to read Barry Dickens’ latest book, Unparalleled Sorrow, a deeply personal account of his battle with depression, his time in a psychiatric ward and his experience of Electro-convulsive therapy.

2008: His year of living precariously

In 2008, Barry Dickins, the Melbourne writer, had a break down. He sank into a deep depression. Unparalleled Sorrow is his harrowing account of his experience of the mental health system and its responses to a man depressed.

The American transcendentalist, Emerson, once wrote that he foresaw a time when fictions would be replaced by memoir – when writers would write directly of the life experience, honestly, without artifice. Unparalleled Sorrow is such a book.

The book is in three sections. The first deals with his months in The Clinic – the hospital to which he admitted himself for psychiatric treatment, the place Dickins describes in his dedication as ‘that wretched clinic’ where he spent ‘six awful months’.

When he finally leaves, the ward assistant takes him aside: ‘Don’t come back!’ Dickins observes: ‘That was his advice and I took it. I’ll never go back to that kind of bastardry.’

‘That kind of bastardry’ took many forms. He describes his psychiatrist as ‘the epitome of haste’, a man convinced that he is right. ‘His Trinity College voice is superior to my Keon park voice. He is always impatient, and never listens to me.’

The routines of the hospital are torture. He is woken at two in the morning by the nurse doing her rounds. One of the things that has brought him to this low ebb has been his insomnia and anxiety; and part of the hospital’s regime is enforced insomnia. When he doesn’t eat, he is bullied by the nurses.

But the worst of the Unit – as the psychiatrist insists on calling it – is the ECT: ‘as you so meekly and thoroughly comply to the obscenity of electrocuting your mind, your poet’s mind, you often feel the jig is up. The most depressing aspect of clinical surrender is your own compliance. Your dumb meekness. You who are no longer, you have agreed to someone you instinctively loathe … The hardest thing about ECT is the complete isolation of one’s impending loneliness of spirit.’

The second section traces the origins of his ‘illness’. Barry describes his origins as working class. It’s true that he grew up in Reservoir, a working class suburb, but his father’s occupation was that of the skilled artisan. Len Dickins was a printer, and – from Barry’s account – a skilled and hard working man who set up a printing press in his back yard shed and worked weekends as well. From his time of growing up in Reservoir, it traces his leaving home, and the years he spent in communal living in St Kilda, and the shocking events he witnessed there. From Barry’s account, the family seems a pretty stable, reasonably happy one. But what family is truly happy? And for how long?

Barry’s mother also suffered depression. In the 1950s there was an ad on the radio, encouraging women to deal with their problems with a simply solution: ‘a cup of tea, a Bex and a nice lie down.’ With the passing of years, she became utterly addicted.

It was a path he too would follow: ‘I caught the bug to drink alcohol at twenty one and drank pots of beer with anyone I met… I began to adore it, whatever it is it seems to cure life or loneliness. But alcohol is loneliness. I grew up in a drinking culture. You drank or were considered a bore if you did not imbibe.’

Barry acknowledges his propensity for self defeating, even self destructive habits.

In his early twenties, away from the steadying influence of home, he joined a commune in Windsor. Many of the people living there were ‘homeless’ people. The house is ‘taken over’ by two men from a religious cult. One murders one of the other house-members by smashing her head on the floor again and again. This incident seems to have been the central event in destroying Barry Dickins’ spirit.

He later marries, but by his own account is too unreliable, to easily distracted – or perhaps just too troubled by the terrible memories that haunt him: his mother’s mental illness, the murder of a woman he liked very much. He and his wife have a son whom Barry clearly adores.

Despite the breakdown of the marriage – it occurs just before Barry goes into the Unit for treatment – Sarah and their son visit him regularly in hospital. And in time, he recovers sufficiently to ‘resume’ his life. And this book, Unparalleled Sorrow, bears witness to this resumption.

The final section, ‘And now …’ is a summing up.

The final section, ‘And now …’ is a summing up.

He begins the book with a quotation from van Gogh, who wrote:

‘With this mental disease I have, I think of the many other artists suffering mentally and I tell myself that this does not prevent one from exercising the painter’s profession as if nothing was amiss.’

I don’t think that Barry would say that he is exercising the writer’s and artist’s profession ‘as if nothing is amiss.’ For much is clearly amiss, and this book is testimony to that.

There is a moment at the every end of the book that will speak to every aging man, and perhaps every aging woman. He writes:

‘One of the aspects of aloneness that is unbearable in never to be touched. The intimacy of being touched is almost beyond my remembrance these days as I go to bed alone and always sleep alone, dream and nightmare alone, never being kissed by anyone else and listening to one’s breath … To be willingly kissed and caressed and kidded and made love to without ever tiring is what I am after each day without success.’

Dickins ends his book by saying: ‘people are hard now and frightened of not being hard’.

I think Barry would say he is now a better man, a more aware man, for what he has been through. His book is deeply moving, deeply touching. I’ve read many of his books. IN my view, this is his best. We can only hope that the unbearable loneliness will pass. For ‘without it, there is … life-hating cancerous vile depression. It devours happiness…’

It is that unbearable loneliness that each of us fears most – more than death even. It’s why so many of us drink or drug ourselves into ‘that best wisdom, which is not to know.’ At times I have regarded the claim that writers are courageous people as a dubious one. It sounds a bit too self congratulatory, too self promoting. But it must have taken incredible courage for Barry Dickins to write a book that is so honest, so free of artifice.

It is that unbearable loneliness that each of us fears most – more than death even. It’s why so many of us drink or drug ourselves into ‘that best wisdom, which is not to know.’ At times I have regarded the claim that writers are courageous people as a dubious one. It sounds a bit too self congratulatory, too self promoting. But it must have taken incredible courage for Barry Dickins to write a book that is so honest, so free of artifice.

It is a book that deserves to be read, written by a man whose honesty and courage are inspiring: this is his finest work.

Leave a comment